by Mackenzie Welch

Whether you enjoy them as a delicacy, or use their shells for Christmas lights or wreaths, bay scallops are a symbol of Nantucket. The bay scallop population acts an important commercial and recreational fishery to the island. It is also one of the last remaining wild bay scallop fisheries. However, the Nantucket bay scallop has been on a gradual decline, with 2019 being cited as the worst scallop harvest in recent history. In an effort to sustain their population, several studies have been conducted to understand their survival, longevity, and population status. But there is one on-going study that has been examining the spawning status of Nantucket bay scallops for over a decade and is encouraging people to understand the importance of bay scallops.

The chief investigator of this scallop project is Dr. Valerie Hall. Her involvement with bay scallop research dates back to the early 1980s, when she conducted research on rearing scallop larvae. After retiring from 35 years of teaching at Nantucket High School, she decided to pursue her doctorate, again her interest being bay scallops. “My focus was the reproductive biology of the species, including the impact of the second spawn and the dynamics of the population of scallops in Nantucket Harbor,” she says. Hall spent six summers gathering data, as part of the Maria Mitchell Association bay scallop research team to use for her doctoral dissertation, which was completed in 2014.

After receiving her doctorate, Hall continued with the Maria Mitchell bay scallop research. From 2005-2012, the lab resided in the Coast Guard boathouse at Brant Point. But because the boathouse was renovated into a shellfish hatchery, the lab found a new home in the Natural Science Museum generously offered by the Maria Mitchell Association. Thus, the current program began in the summer of 2016.

The objective of this research is to examine the scallops’ reproductive organ, or gonad, and determine its reproductive status. Bay scallops are hermaphrodites, meaning they have both a testis and an ovary. Scallops are brought in from the field and dissected to remove their soft body and to separate their gonad. Those tissues are weighed individually because those values are used to calculate the GSI of each scallop. “The GSI is the ratio of the gonad to the body weight, it varies throughout the season, being highest right before the scallop spawns,” says Hall. The rest of the procedure consists of preparing the gonad for histology, which is the process by which tissues are prepared for microscopic examination. The end result of their research is a microscopic slide of a cross section of a scallop gonad. With the slide, they can determine if the scallop is immature, ripe, spawning, or past spawning.

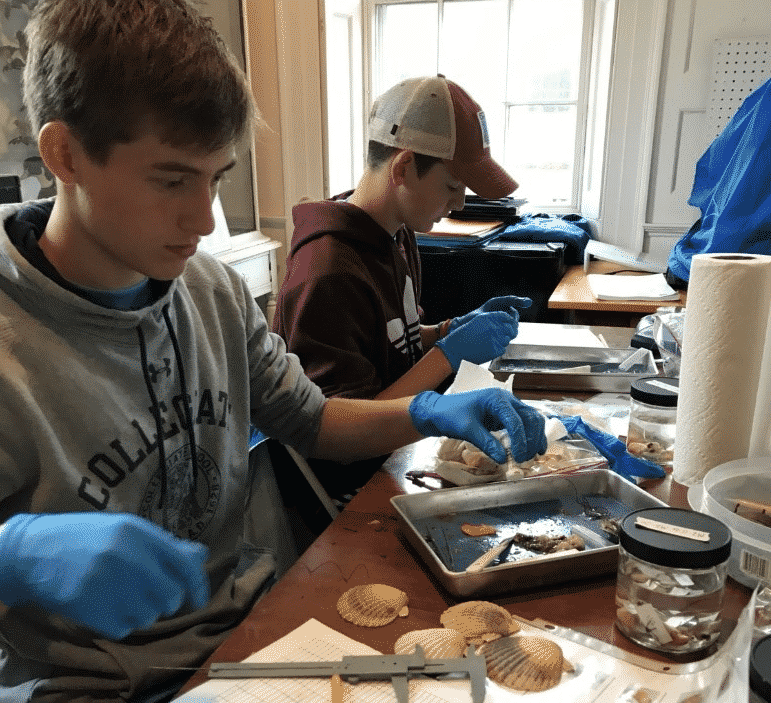

Hall’s scallop lab is not just a place for research; but it also provides an educational experience to students interested in the field of biology. Hall recruits students from Nantucket High School, where she encourages them to get involved. Some students are inspired to join the project. “I wanted to work in the lab because I wanted to learn about how our current climate is affecting a vital species here on Nantucket,” says Katie Purda, a junior at Nantucket High School and recent lab volunteer. During the program, students are able to participate in every aspect of the scallop research. Some students even create independent projects that are mentored by Hall. Volunteering in the lab has helped some of the students advance in their education and careers. “When I moved from Nantucket, this research experience was crucial for me to land an internship in a pediatric oncology lab,” says Nischal Khatri, a senior at Medford High School and former lab volunteer.

Local recruitment seems to do the trick, as the lab is constantly growing in numbers of volunteers. “The program grows every year; last summer there were 12 students who spent an average of two days a week in the lab,” says Hall. While the research is important, Hall takes great pride in seeing the students working together. “They become a close-knit, cohesive group, working together toward a common goal,” she says. Unfortunately, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, there will be some restrictions in the use of the lab this summer. But with faithful students wanting to return and major funding from the Nantucket National Shellfish Association, Hall is excited to get the program up and running again. With the scallop spawning season starting, it is guaranteed that the lab will be getting back to work soon.